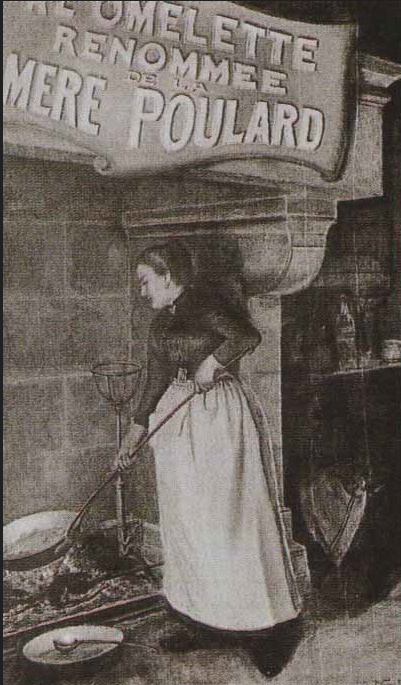

Ideally situated in the heart of Mont Saint-Michel, come and discover the legendary Auberge, founded in 1888 by the famous chef Annette Poulard.

Come and experience Auberge La Mère Poulard

A unique experience

Push open the doors

de l'Auberge

La Mère Poulard is much more than a name: it's a heritage, that of Mont Saint-Michel and a culinary tradition rooted in French heritage. It's a story of indulgence and generosity.

Above all, La Mère Poulard is the story of Annette, a woman driven by a love of sharing and the joy of entertaining, who ensured that everyone left with a light heart, a smile on their face and the desire to return sooner or later to sit down at her inn.

Accommodation

Annette welcomes you to her houses

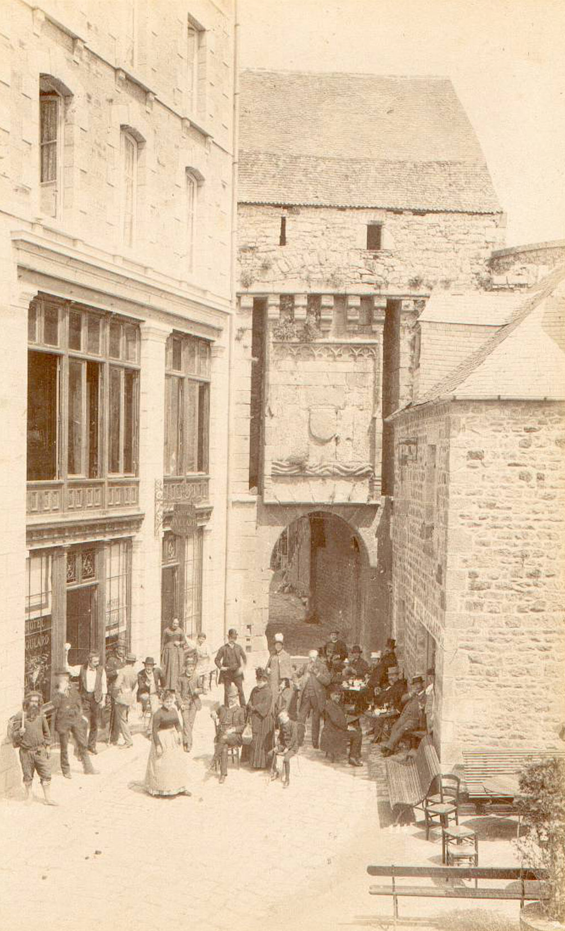

From the Auberge Historique to the Maisons d'Annette, each of La Mère Poulard's signature establishments promises a timeless experience. Staying here is much more than just a night in the heart of Mont Saint-Michel. It's an immersion in history, in the footsteps of Annette Poulard herself, where she welcomed travellers, the curious and celebrities, offering them a warm and unforgettable welcome.

Historic Auberge

Taste the legend in the house where the Mère Poulard omelette was born.

Maison rouge

Stay in a charming residence with its own secret garden.

Hermitage

Take a rest in Annette Poulard's last house, which is full of serenity.

Maison de l'Epée

Enjoy an intimate stay in the heart of Mont Saint-Michel.

Maison de L’artichaut

Live like a true Montois in this authentic medieval house.

Historic Auberge

Taste the legend in the house where the Mère Poulard omelette was born.

The Auberge restaurant

Tasty and generous traditional cuisine

The Auberge La Mère Poulard is where it all began. Over the decades, its iconic restaurant has welcomed countless celebrities who have come to sample its unique charm. Ernest Hemingway, François Mitterrand, Pablo Picasso... and so many others have left their mark here. But what if the Auberge's real claim to fame wasn't the soufflé omelette that Annette creates and jealously guards its secret?

What visitors say

Organising an event

Groups & Seminars

Take advantage of the exceptional and majestic setting of La Mère Poulard and its hotel in Mont Saint-Michel for your group stays or seminars. You'll benefit from a wide range of services designed to ensure that your stay, whether professional or private, runs smoothly.

We provide you with welcoming, flexible spaces that combine historic charm with modern comfort, to make your event an unforgettable experience.

Your visit to

Mont Saint-Michel

There are places that invite you to marvel, places that are more magical than others, places that are not just steeped in history but that make history. Mont Saint-Michel is one such place.

And if Mont Saint-Michel is as famous as it is, it's partly thanks to La Mère Poulard and its famous omelette...

Immerse yourself in the thousand-year-old history of this emblematic island, discover its picturesque narrow streets, its majestic abbey, its breathtaking panoramas and, above all, its shared past with Annette Poulard.

Plan your getaway now with this site full of practical advice and ideas for activities.